WORK SHOP ABOUT SWAP EDITIONS OBJECT | MULTIPLE

> EILEAN SHONA RESIDENCY MARCH 2024

A month of off-grid residency time living alone in a cottage in the woods on Eilean Shona - a stunningly beautiful car free wilderness island on the west coast of Scotland. This opportunity was awarded by the Royal Society of Sculptors, and kindly supported by Vanessa Branson. Thank you!

A month of off-grid residency time living alone in a cottage in the woods on Eilean Shona - a stunningly beautiful car free wilderness island on the west coast of Scotland. This opportunity was awarded by the Royal Society of Sculptors, and kindly supported by Vanessa Branson. Thank you!

"Until the middle of the 18th century, Eilean Shona was populated with a number of crofters. The main house was a small hunting lodge owned, in the middle of the 19th century, by the seafaring Captain Swinburne. He collected numerous types of pine on his travels and established what became one of the most diverse Pinetums in Europe. At the end of the 19th century, Robert Lorimer, who planned much of Edinburgh's New Town, was commissioned by the island's owner, a Mr. Thompson, to remodel the main house, doubling its size. In the 1920s J.M. Barrie rented Eilean Shona for the summer as a holiday home, where he was joined by Michael Llewelyn Davies and some friends. It was Michael, along with his four brothers, who had been the inspiration for J.M. Barrie's characters Peter Pan, the Darling brothers and the Lost Boys. Barrie is thought to have worked on both the screenplay of Peter Pan and the ghost story, Mary Rose, while on Eilean Shona" read more about the island at www.eileanshona.com.

A month of breathing fresh air and talking to myself while getting lost exploring the remote island terrain while secretly pretending I’ve been shipwrecked - magic.

A month of breathing fresh air and talking to myself while getting lost exploring the remote island terrain while secretly pretending I’ve been shipwrecked - magic.

For my residency on Eilean Shona I took with me boxes of old photographic paper and cyanotype solution, a sculpture kit of mould-making and casting supplies, my camera and a large roll of bright orange gaffer tape.

Sculpture is at the heart of my practice, but I also planned to incorporate making work in print and photography. Working with whatever treasure the island revealed encouraged an experimental approach to collecting forms and images. It was the perfect opportunity to combine analogue photographic processes with physical things and tactile surfaces, creating prints from a very sculptural mentality. My aim was to step away from city life and take a breath to explore a sense of wonder about the island while being off-grid and out of signal. A rare opportunity to slow down, go walking and make curious discoveries. To think about deep time, big landscape and being alone, digitally disconnected in the wild.

The act of walking, finding and collecting is a big part of how I engage with a place and I was constantly foraging the flotsam and jetsam washed ashore. In an environment where the weather ensures nothing is permanent, finding curious perishable material to petrify as solid forms via mould-making and casting was always on my mind. I often found myself drawn to the abundance of seaweed lining the shores and the lush moss that blanked the forrests as sources for inspiration.

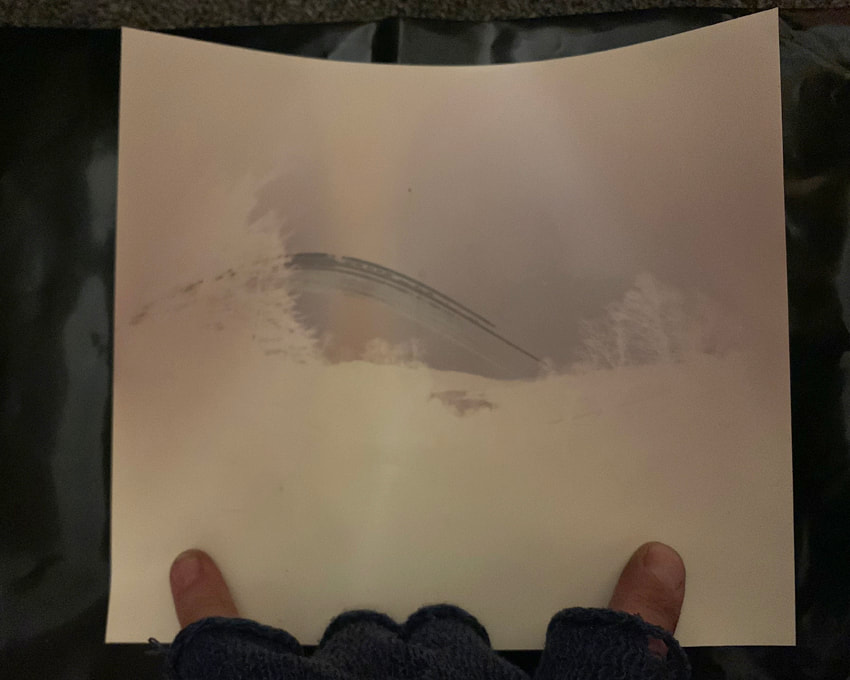

I intended to use whatever resources were at hand to make work while away from my familiar surroundings, and find my own and visual language on the island. In the cottage I embraced a DIY approach and turned the corridor space by the fridge into a make-shift darkroom. I constructed pin-hole cameras from empty food containers and located them out in the landscape. Going analogue enabled me to create long exposure images that recorded the same light duration of lunar cycles as I physically had on the island. By preparing a set of pin-hole cameras on the day I arrived meant I have images that represent a complete months worth of time. I spent a lot of time at all hours of the day and night in the forrests and down on the loch side - and neither was as dark or as silent as I’d imagined. Stars are bright and wildlife is loud. I wanted to respond to the feel of the island and create soft grainy works from within my temperate landscape surroundings.

Maybe it was being away in an ancient landscape or simply the isolation of being on my own. I found myself thinking a lot about the ephemeral nature of the things around me, and how to capture a sense of alchemy in the work I produced during my month on the island. I’d initially taken the photographic paper to make pin-hole cameras, but by playful disrupting the light sensitive material I could also make photograms, much like the original botanic camera-less photography of the 1800s. My old Silver Gelatin Paper produced images rich in colour that were further enhanced by the changing light, long exposures and playful contaminations from the things i’d foraged. The notion of venturing onto a wilderness island on my own to create a set of forever unfixed photographic works that can’t be shown to anyone seemed almost magic in itself.

My parting gift to the island was installing a set of long exposure pin-hole cameras in various fixed locations to remain for a full year, or at least as long as the elements allow.

Sculpture is at the heart of my practice, but I also planned to incorporate making work in print and photography. Working with whatever treasure the island revealed encouraged an experimental approach to collecting forms and images. It was the perfect opportunity to combine analogue photographic processes with physical things and tactile surfaces, creating prints from a very sculptural mentality. My aim was to step away from city life and take a breath to explore a sense of wonder about the island while being off-grid and out of signal. A rare opportunity to slow down, go walking and make curious discoveries. To think about deep time, big landscape and being alone, digitally disconnected in the wild.

The act of walking, finding and collecting is a big part of how I engage with a place and I was constantly foraging the flotsam and jetsam washed ashore. In an environment where the weather ensures nothing is permanent, finding curious perishable material to petrify as solid forms via mould-making and casting was always on my mind. I often found myself drawn to the abundance of seaweed lining the shores and the lush moss that blanked the forrests as sources for inspiration.

I intended to use whatever resources were at hand to make work while away from my familiar surroundings, and find my own and visual language on the island. In the cottage I embraced a DIY approach and turned the corridor space by the fridge into a make-shift darkroom. I constructed pin-hole cameras from empty food containers and located them out in the landscape. Going analogue enabled me to create long exposure images that recorded the same light duration of lunar cycles as I physically had on the island. By preparing a set of pin-hole cameras on the day I arrived meant I have images that represent a complete months worth of time. I spent a lot of time at all hours of the day and night in the forrests and down on the loch side - and neither was as dark or as silent as I’d imagined. Stars are bright and wildlife is loud. I wanted to respond to the feel of the island and create soft grainy works from within my temperate landscape surroundings.

Maybe it was being away in an ancient landscape or simply the isolation of being on my own. I found myself thinking a lot about the ephemeral nature of the things around me, and how to capture a sense of alchemy in the work I produced during my month on the island. I’d initially taken the photographic paper to make pin-hole cameras, but by playful disrupting the light sensitive material I could also make photograms, much like the original botanic camera-less photography of the 1800s. My old Silver Gelatin Paper produced images rich in colour that were further enhanced by the changing light, long exposures and playful contaminations from the things i’d foraged. The notion of venturing onto a wilderness island on my own to create a set of forever unfixed photographic works that can’t be shown to anyone seemed almost magic in itself.

My parting gift to the island was installing a set of long exposure pin-hole cameras in various fixed locations to remain for a full year, or at least as long as the elements allow.